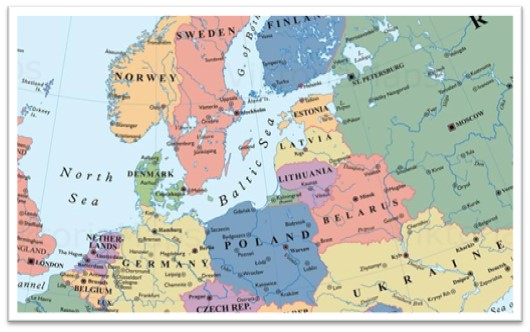

At the northwest corner of Russia, across the Baltic Sea from Sweden, lie three small independent countries: Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia—the Baltics. With a population of just over six million between them, they’re tiny, but generously endowed with fertile soil, natural beauty, industrious populations, and a profitable location for trade.

Unfortunately, that location also placed them in the crossfire of two warring and acquisitive giants of the 20th century, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. The Baltics’ diminutive size rendered them defenseless, chronically occupied, and brutally abused, alternately by both countries.

During their many years as part of the Eastern Bloc, the Baltics were rarely explored by Western travelers. And even though the doors opened when they gained independence in 1991, Westerners are only now discovering their rich history, art, architecture, and welcoming spirit.

In the spring of 2015, I recruited two old friends and my father-in-law to visit them.

Despite many destructive wars over the centuries, Vilnius is impressively preserved and restored. Its Old Town features cobblestone streets, ancient churches, a 16th-century university, Baroque buildings, spires, and turrets. Walking the narrow winding streets transports you back centuries to a busy university town with students from across Europe.

But a tragic history soon appeared among the charm and historic elegance. Vilnius’ Museum of Occupations, locally called the KGB Museum for its location in the former KGB headquarters, is a memorial to the Lithuanian dissidents and freedom fighters the KGB interrogated, tortured, imprisoned, and murdered here. A guide explained the tools of torture, including tiny dark cells for solitary confinement and a basement room where more than 1000 Lithuanians were executed, their bodies hauled away in trucks to anonymous mass graves.

Similar histories were recounted to us many times in all three Baltic countries. It is a theme that permeates the national character and psychology.

Between the World Wars, the Baltics gained independence from their various occupiers. But in 1939, Hitler and Stalin made a secret pact to divide Europe between them; the three Baltic countries were assigned to the Soviets. The Red Army soon invaded and occupied them, they were incorporated into the Soviet Union, and Russian language and communism were imposed. Baltic resistance was widespread, but quashed with imprisonment, execution, and deportation.

In 1941, the Nazis broke the pact and invaded, invoking their own laws and language, and killing over a quarter million Baltic Jews.

At the end of WWII, the Soviet Union again occupied the Baltics, resuming repression and deporting an estimated 10% of the adult population to gulags or remote Soviet locations. Farms and industry were confiscated for collectives and state ownership.

Armed resistance groups formed repeatedly, only to be repressed, defeated, deported, or executed. Nevertheless, the Baltic people continued to resist—eventually with “singing revolutions.” On Aug 24, 1989, a two-million-person human chain stretched 600 km across the three countries and sang freedom songs. The Soviets felt the building pressure and, in 1991, recognized Baltic independence, precipitating the complete collapse of the Soviet Union.

It seemed every Baltic person had a tragic personal story from that era. Our group leader, Erika, told us through tears how Russians appeared at her grandparents’ door late one night and took her grandfather away; the family never saw him again nor found out what happened to him.

On two evenings our schedule included discussions with local government officials/historians about “our struggle for independence.” The recurring topic seemed not so much chosen for tourists, but because it was the all-consuming existential concern of the Baltic people.

In our conversations with locals, a subject that frequently arose was Russians in their countries. During the Soviet years, the Baltics were the most prosperous of the Soviet states, drawing so many Russians that native people were nearly outnumbered. When the Baltics achieved independence, most bureaucrats and government employees went back to Russia, but other Russians remained.

The bitter history as well as ethnic differences continued to annoy many natives, and the Russians were the butt of many jokes, most of which seemed more a release of pent-up frustration and bias than funny.

In Rumsiskes, Lituania, we visited an open-air museum of 18th and 19th century rural dwellings and farmsteads. Full-size reproductions offered a detailed and up-close view of rural Baltic life.

But the outdoor museum also included an old train car and a crude sod hut. An elderly lady who manned the exhibit described how at age 8, she and her family were rounded up by the Russians late one night. Her father was separated from the family and never seen again. She, her 12-year-old brother, and her mother were locked in a crowded train car like the one exhibited and shipped off. Thirty days later they were unloaded in northern Siberia near the Arctic Circle.

They had to quickly build a shelter because winter was setting in, but there were no trees nor materials. They dug sod from the cold earth with their hands to make a crude hut, and with one coat and no food between them, nearly froze and starved that winter.

Thirty five years later she made her way back to Lithuania but found herself unwelcome—her friends and relatives were gone, and others were afraid to associate with her because she had come illegally. Not until Baltic independence was she again legal in the country where she was born.

Nearly every person we met in the Baltics readily expressed how happy they were to be free. As one man told us, “Life is much better now. The economy is stronger, we can choose our work, go to church, own businesses, and travel. And tourists are beginning to come.”

Baltic Reflections: Freedom is Dear To Those Who’ve Lost It

The Baltics are a pleasure to travel. Everything works: the streets are clean, buildings well maintained, traffic flows smoothly, hotels are quiet and comfortable, restaurants serve tasty food efficiently, store shelves are stocked, etc. Long lines were rare because systems and people worked. It was the essence of northern Europeans. Pity their neurosis but admire their results.

An old travel adage says, “To know a people study their history.” In the Baltics, years of abuse left psychological scars. Being helplessly occupied and re-occupied was undoubtedly traumatic; deportations, splitting families, labor camps, mass executions, and genocide are horrors that permanently imprint the human mind and forever haunt its soul.

Their tragedy was their size—they had no hope of defending themselves against the powerful and acquisitive countries surrounding them. Like helpless pawns, they watched in fear as their adversaries determined their very existence.

The weapon they ultimately devised, the singing revolution, was brilliant and potent. While the Soviet Union was portraying its communist system as social utopia and the future of the world, turning eyes toward its failures and the Baltics’ unhappiness was a stinging rebuke and embarrassment. The tactic not only made possible their independence, it set off the dissolution of the weakening Soviet Union.

Once free, the Baltics mounted a successful campaign to join NATO, achieving the defense they so desperately wanted but would never achieve alone.

From such history, we can appreciate the consuming preoccupation with independence that we found at every turn. It also created a deep appreciation of their freedom for which they paid so dearly.