For my generation, “Vietnam” evokes images of guerrilla warfare in steamy jungles on the other side of the world, fighting an invisible but deadly enemy, for a cause we never understood. It was the hell Uncle Sam sent us to if we didn’t stay in school. It went on far too long and took too many lives for it to be a patriotic adventure—it was a bloody horror show with no ending.

Today Vietnam is a vacationland and tourist mecca. Golden beaches, lush mountains, colonial architecture, temples and pagodas, thriving metropolises, world famous cuisine, and welcoming people beckon tourists from all over the world. 18 million answered the call in 2019, including 400,000 Americans.

In 2008, my industry travel buddies, Paul Heid and Steve West, and I met to choose our stops on the way home from a Shanghai convention. Vietnam was one we easily agreed on. We’d heard glowing reports of it as a tourist destination and perhaps we wanted to reconcile that with the impressions of our youth.

The morning after our late night arrival in Hanoi, I was still off schedule by several hours. By the time the sun came up I was dressed and pacing the room. I decided to take a stroll outside the hotel.

As I walked a young guy road up on a motorbike and asked if I needed directions. I didn’t but his English was good, and we started a conversation. He recommended a few things to see in Hanoi, including tiny Huu Teip Lake, his directions to which progressed to “Hop on.” I did.

Hanoi wasn’t up yet so we didn’t have to navigate the seas of motorbikes. We crossed the city and were weaving through the backstreets of a neighborhood when it occurred to me that I was an easy target for kidnapping—if he pulled into a garage, no one would have known where I went or how I disappeared. I was scanning the street for a suitable spot to jump off when we arrived at our destination.

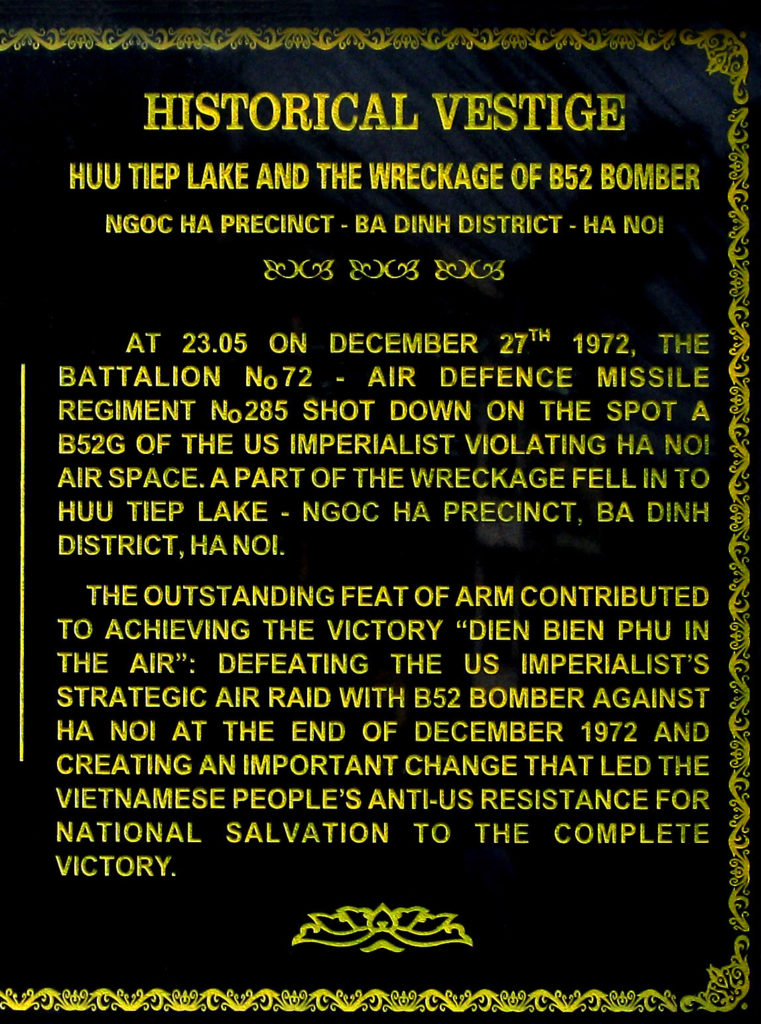

Huu Teip Lake’s fame is that in 1972 North Vietnam shot down an American B-52 and a large part of it fell in the lake—a pond really, tucked between homes and apartments in the middle of Hanoi.

The debris remained, sticking up in the water as an ugly but poignant monument, complete with a plaque in both Vietnamese and English.

I spent a few minutes in silent contemplation, struck by both the gravity of the scene and the paradox of my current situation—a North Vietnamese host graciously (or maybe just gainfully) guiding me through the American wreckage of the Vietnam War.

I asked if he had lost family members in the war. He had—an uncle, and his father lost a leg. But I didn’t detect any emotion in his answer. He was too young. All his family’s pain, suffering, and losses in 20+ years of war were probably barely a part of the factual paragraph or two passed on to him.

We rode on, past the Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum, the Temple of Literature, and the One Pillar Pagoda, toward the Old Quarter for some egg coffee.

Hanoi was awake now and scooters and motorbikes flooded the streets like tsunami waves. Intersections resembled two great rivers crossing, merging smoothly into one and then emerging on the opposite side, undeterred in their original paths. It was an impressive feat of balance and control for the cyclists, especially those with multiple passengers.

It was a little after 8 am when he dropped me back at the hotel. I tipped him well for the tour and his bike acrobatics—and for not kidnapping me.

I was late for breakfast, and Steve and Paul were already seated, no doubt assuming I overslept. As we discussed sights we might want to see that day, I mentioned that I’d already seen some of them that morning but was willing to go again. They were sufficiently incredulous that I should have made big bets with them before sharing my pictures as proof.

The War Museum was our first stop. In the courtyard was a B-52 bomber standing on its nose, surrounded by a destroyed “Huey” helicopter, an F-5A fighter, a “Daisy Cutter” bomb, an M48 Patton tank, and a junkpile of powerful US weapons—an ominous preview of what awaited us inside.

In the “American War” building were war paraphernalia of both sides, a full-size jungle diorama, and graphic photography of the effects of Agent Orange and napalm. Descriptors like “imperialist,” “aggressor,” “heroic struggle against mighty invaders,” “severe resistance war” demonstrated startling but understandable differences in perspective and served as a reminder that each country writes its own history.

But we also noted that the museum had opened in 1975 as the “Exhibition House for US and Puppet Crimes,” became the “Exhibition House for Crimes of War and Aggression” in 1990 as relations with the US warmed, and was renamed the “War Remnants Museum” in 1995 upon the end of the US trade embargo. Economics has the power to revise history.

As we walked the streets and through parks, students and young people approached us multiple times, wanting to talk or take pictures with us. That’s not unusual in Asia, but in Vietnam we were more than just Western novelties sticking up in the crowd; they could tell we were American, spoke English to us, and wanted to talk about America, pop music, and movie stars. The new generation of Vietnamese was refreshingly ignorant of the war and not only eager to be friends, but to absorb our culture.

In our youth we heard much about “The Hanoi Hilton” as American POWs called the Hoa Lo Prison. Hundreds of American pilots and servicemen were incarcerated there, including Senator John McCain and Admiral James Stockdale. Most of the prison had been torn down for new development, but a portion remained as a museum, apparently to show the world how poorly the French, who built the prison, treated the Vietnamese, and how well the Vietnamese treated the Americans. Its description piqued our interest.

Exhibits included models of cells and leg shackles the French used on the Vietnamese—cruel indeed.

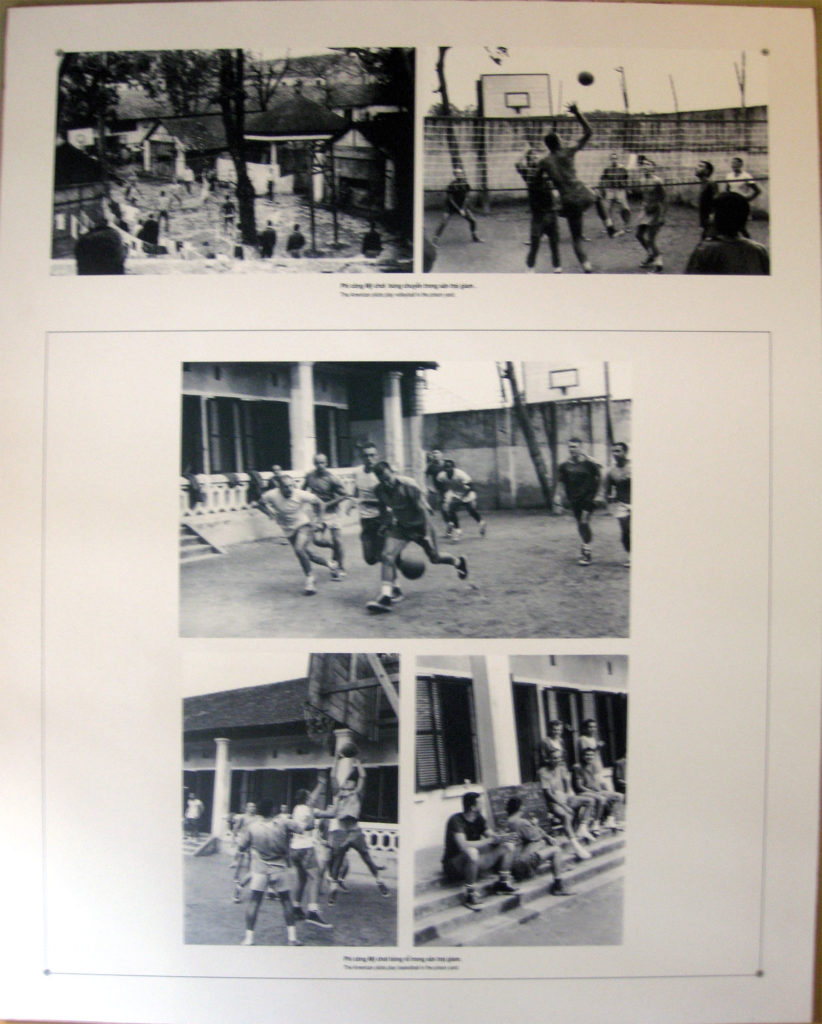

In the American War section were photos of American POWs playing basketball, chess, and pool, and enjoying a Christmas dinner. Descriptions and a video said POWs got good medical care, received care packages from home, and could talk to reporters and humanitarian agencies. According to one exhibit, conditions were so good the prisoners named the prison after the luxury hotel chain.

Surviving POWs tell a different story, of beatings, broken bones, starvation, irons, and for some, years of solitary confinement. History has multiple perspectives.

While Hanoi is the government and political center of Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon) is the center of business and industry. Our musical instrument stores were buying products made in Vietnamese factories and Steve had arranged for us to visit several in Ho Chi Minh City.

The first was owned by a Taiwanese company that made a private label line of brass instruments for us. One of the Taiwanese owners picked us up at our hotel for the 2-hour trek into the Vietnamese countryside.

The ride was a taste of rural Vietnam—barefoot men and women in wide conical hats herded cows or waded through paddies of rice. Broad hedges of bamboo separated paddies and plots. The only machinery visible was abandoned US tanks on the side of the road.

We pulled off the highway and down a long narrow lane lined with dense foliage, where a small colonial building came into view. One car and several motorbikes were parked in front.

After a quick round of introductions to the factory managers, we were led out the backdoor. The factory was an old rusted-metal rectangle with a long row of windows across the top. The age of the factory and architecture of the office signaled the French Colonial period, before the French tired of Vietnamese rebellion and ceded the problem to America in the 1960s.

Bicycles lined one side of the factory building, begging the question of how far they had come, as no other civilization was in sight.

The factory was the antithesis of modern manufacturing—dark and dingy, few modern machines, workers scattered randomly at old desks, tree stumps serving as work surfaces. Still the craftsmen were agile and skilled with their crude tools, and by the end of the line, the instruments were smoothly functioning, impressively finished, in-tune, and arguably the best bargains on the world market.

Corrugated shipping boxes awaited, some printed with our brand name, many others with some of the biggest brands in our industry.

The second factory provided a stark contrast—huge, new, brightly lit, modern machinery, long rows of perfectly aligned benches, hundreds of workers at identical sewing machines. This was the new Vietnamese economy, making our clothes, shoes, and untold other “cut-and-sew” products. A tiny portion were musical instrument bags.

And finally, a small guitar factory. It was owned and operated by a young Chinese entrepreneur who chose Vietnam for his venture because wages were rising in China and he felt the Vietnamese business and manufacturing climate was more promising. He was dedicated, living and sleeping in an upstairs factory office and returning to China only a few times a year to see his family.

The quality had a ways to go, but if Vietnamese wages stayed low and he could keep his employees until they developed their skills, he’d likely realize his dream.

No business hosting in Vietnam is complete without a few rounds of beer. Four Vietnamese factory managers took us to their favorite restaurant and ordered a case of beer, glasses with ice, and a lazy-Susan load of mystery dishes.

They gave us a quick course in Vietnamese beer drinking: When someone says “Mot, hai, ba, yo,” everyone takes a drink; when a troublemaker toasts you with “Một, trăm. phần. tram,” you and they chug the rest of your beers. It’s a contest Vietnamese are fond of, particularly against Westerners. One female manager apparently trained regularly, took great pride in her skills, and won handily.

Vietnam Reflections

Despite Vietnam’s natural beauty, colonial architecture, distinctive lifestyle and culture, and gracious people, my thoughts were consumed by the evolution of its relationship with the US. And that in turn raised more questions than I could answer. For example:

How is it possible for two countries to fight one of the bloodiest wars of the century, killing and maiming each other en masse, and then become “comprehensive partners?” How can Vietnam in a matter of years be “our closest ally in Asia?” How can 76% of the Vietnamese people have a “favorable” opinion of the US? How can Vietnam now be a vacationland for Americans?

What changed? Did one country suddenly “see the light?” …do a complete makeover of character and ethics? Or were our differences so inconsequential that we’ve forgotten about them? Are the values we fight and die for so fickle and fleeting?

What was so important to us that we were willing to send our sons and daughters off to kill the sons and daughters of another people? If it was differences in ideas of governance, couldn’t we have had a civil conversation about them? If people with the same information come to the same conclusions, wasn’t it worth exchanging information?

And if one form of government is truly better than another, wouldn’t time prove that without us having to kill each other? Couldn’t we get those answers less disastrously from history and research than warfare?

When we declare war, do we realize what we’re getting into? Did we know the Vietnam War would last 19 years and take 58,220 American lives? The Korean War 3 years and 36,574 lives? The Gulf War 1.5 years and 383 lives? The Afghan War 19 years, 2,216 lives, and still fighting? The Iraq War 17 years, 4,497 lives, and still fighting?

What about the casualties and destruction on the other side? Do they count too? Or do our philosophical differences make their losses inconsequential—or even desirable?

Which of these wars were worth fighting? If we had a do-over with full understanding of the consequences, which would we fight again?

Can any war ever really be won?

Isn’t there a better way?

Or is it simply unpatriotic to ask?

One of our greatest generals, Dwight Eisenhower, delivered a powerful speech on war just before he retired from the Presidency. Here’s an excerpt:

“Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, from those who are cold and are not clothed.

“The world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children.

“The cost of one heavy bomber could build modern schools in 30 or more communities, or two fine, fully equipped hospitals. We pay for a single destroyer with the money for new homes that could have housed 8,000 people.

“This is not a good way of life in any true sense. Under the cloud of threatening war, it is humanity hanging from a cross of iron.”