India is more than a country—it’s a subcontinent with huge diversity, from golden sand beaches to snow covered Himalayan mountains, from desolate deserts devoid of wildlife to verdant jungles inhabited by elephants, leopards, and tigers. It is home to almost 18% of the world’s population, over 19,000 languages, and four of the world’s major religions.

Its borders contain the world’s most beautiful architecture and most destitute slums. It is at once the inspiration of great art, literature, and design, the hopelessness of poverty and over-population, the sensual assault of the streets and crowds, the calming of yoga and meditation, and the exasperation of bureaucracy and corruption. There is simply too much of the world’s history, culture, human condition and experience to miss.

India had long been on my bucket list, but it isn’t on the way to anywhere and getting there is an epic expedition.

In 2008, my friend, Paul Heid, and I represented our trade association at a convention in Shanghai and decided to take the long way home. We made a list of possible stops, and India, specifically the Taj Mahal, was high on it.

We had only a couple of days in India, so our plan was to catch a fast train in Delhi to Agra (120 miles), spend a couple of nights, and return to Delhi for our flight out. But in India, things rarely go according to any plan.

Our plane arrived on time and we quickly made our way to the train ticket booth. We had nearly an hour before the train departed, and although there were twelve people in line in front of us, the process appeared quick and efficient.

A couple of times while we waited Indian men approached us and offered to help us get our tickets, no doubt for a fee; we politely declined. But after 45 minutes in line we hadn’t moved and there were fourteen people in front of us. As we looked closer, we could see the ticket seller waving those “ticket helpers” to the window while the line waited. Too late we figured out that the ticket helpers were splitting their fee with the ticket seller. If you didn’t pay a helper, you might never get a ticket.

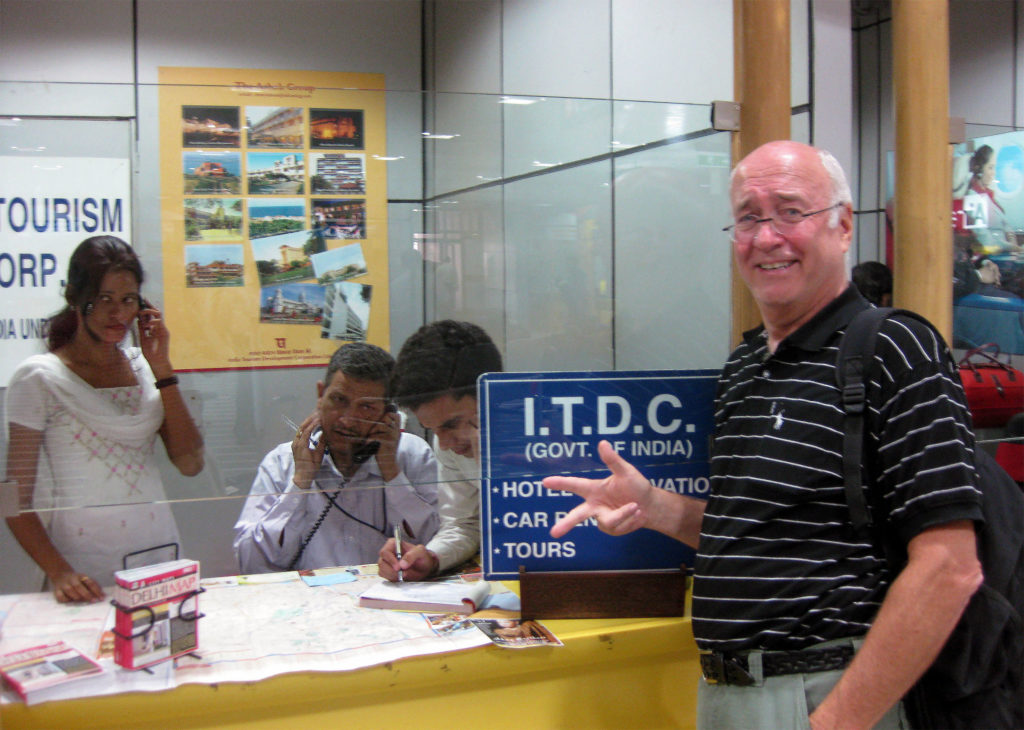

We’d missed the fast train, so we began looking for other transportation. The arrival hall was lined with “Official Government of India Tourism” booths, most of which advertised cars and drivers. We checked with one. He didn’t seem to hear our transportation needs but was laser-focused on where we were staying in Agra. He told us our hotel had just had a fire and wasn’t open, but he’d arrange another for us.

We tried another booth. This time our hotel was “closed for renovation,” but she’d find us another. The third said the Taj Mahal was closed that day but he could arrange a hotel for us in Delhi.

Sensing the challenge, Paul and I split up to double our inquiries. Within a few minutes Paul motioned to me; an agent offered a car and driver for two days for $140. As soon as we accepted and paid, all three employees got on their cellphones, searching for someone with a car.

A couple of hours later a guy showed up in a Tata Nano, the world’s cheapest car ($3000 brand new). We crammed our carry-ons into the front seat next to the driver and squeezed into the back, our backpacks in our laps, telling ourselves it was only for 120 miles.

A few miles outside the airport, our driver reminded us how hot it was and offered to turn on the air conditioner for $20.

The roads were chaos. Two lanes were used as four, six, or seven, with people driving on the lines instead of between them. It didn’t seem to matter whether you drove on the right or left; they took whatever space was open, relinquishing it only when an oncoming vehicle was bigger. Passing was a game of chicken with winners determined at the last second. Turn signals were used to indicate it was OK to pass as well as for turning; misinterpretation could be fatal.

Buses and open trucks were packed with people, often with more hanging off the sides, back, and roof. Whole families squeezed onto tiny motorcycles.

The cacophony of horns was relentless but with a different meaning. Signs on the back of trucks said, “Honk so I know you’re there.” And they did.

It didn’t take long for us to realize that we’d grossly underestimated how long our journey would take. The highway was a moving obstacle course of pedestrians, cows, elephants, buffaloes, goats, rickshaws, and horse and camel-carts—not to mention large rocks and potholes deeper than our tiny 12” wheels.

Some obstacles were intentionally placed. When we stopped for a pull cart strategically stretched across all lanes, our car was quickly surrounded by peddlers and beggars. A snake charmer with two cobras performed on one side of us, and a forlorn woman holding a dirty baby knocked on the other side, rubbing the tips of her fingers together. When we gave her a few rupees, the crowd became frenzied. Our driver struggled to extricate us and warned us not to do it again.

Multiple times our driver asked if we wanted to stop at various stores to buy jewelry, precious stones, pottery, or carpets. For each, he had “a friend who would give us a very good deal.” We declined, not wanting to prolong our agony.

After six painful hours folded up in the backseat on the bumpy, nerve-wracking roads, we arrived at our Agra hotel. The exterior was impressive only for its barrenness—a high and windowless stone wall, as impenetrable as a fortress; it might well serve as a prison. Inside was a lush oasis, clean, quiet, and luxurious—neither burnt nor under renovation. It was a stunning contrast to the world outside. We were too tired to brave the dark and crowded streets, so we ate in the hotel restaurant. The food, service, and setting were outstanding.

We got up early the next morning to get Taj Mahal tickets. As the line grew behind us, two Indian men stepped boldly in front of us. We resisted our initial inclination to stand up to them, remembering we were in their country; instead, we struck up a conversation and made a deal for them to buy our tickets too. Only a day in India and we’d traded fairness for pragmatism. Within minutes we were inside. Our only concession to guilt was hoping that long line would function better for those behind us than ours had the day before.

The Taj was indeed fabulous, deserving of its reputation as among the world’s most beautifully proportioned buildings. An impressive monument to a young lady who died in childbirth—or was it to the subjugation of a huge population to the whims of a self-absorbed ruler. (Every feat worthy of notice attracts someone’s disparagement.)

Within the grounds, a horde of independent hawkers offered their services and souvenirs. One latched on to us, showing us the best photographic angles. Despite our initial resistance, his guidance proved helpful; we offered him 100 rupees (~$1.40), he suggested 1000, we settled on 200, and parted amiably.

We spent the rest of the afternoon shopping for carpets, pottery, pashminas, and gems, guided by our highly incentivized driver. I had no interest in any of these but always enjoy seeing the handiwork and interacting with the people. Paul likes the buying process more than the products, but regularly brings home more than he has room for. However, on this day, all the gems were flawed, the pashminas were of coarse cashmere, and the carpets were overpriced, even after negotiating 80% off.

At the end of the day we’d bought nothing, much to the obvious dismay of our driver.

Reflections: Circumstances Dictate Ethics

Two days in a diverse and complex country like India doesn’t scratch the surface of the culture. I intend to go back someday with much more time to understand it better.

Yet two days may well represent the initial shock many travelers experience at India’s extremes.

India is historically one of the world’s poorest countries. According to many estimates, over 300 million people live on less than $.50/day and 700 million people live on less than $3/day.

But not all of India is poor. An estimated 106 billionaires, and 350,000 millionaires call India home. A growing upper class enjoys many of the world’s luxuries and status symbols. The disparity between rich and poor is among the world’s widest. The 16 wealthiest people own as much as the 600 million poorest.

For the hundreds of millions at the bottom of the spectrum, daily life is a battle for survival. Finding work and climbing out of poverty is beyond their dreams—they only hope to find enough to eat and a place to sleep each day. What few jobs are available for unskilled workers pay about $1/day and are overwhelmed by long lines of applicants.

In Les Miserables, hero Jean Valjean commits the excusable crime of breaking a window and stealing a loaf of bread because “My sister’s children were starving.” Perhaps the response of India’s poor to a similarly desperate situation should be as understandable and forgivable.

But in India, the sheer number of the destitute takes competition to a new level. Beggars have to dress to stand out in a crowd of beggars; street hawkers can’t attract attention so they kidnap it. Small scams are so expected they’re brazen and fearless; large cons can be surprisingly complex and sophisticated, involving multiple conspirators over several hours or days.

Alleviating poverty is the perennial promise of every politician, but economic development is stunted by the culture of corruption. Many companies have been attracted by abundant and cheap labor, only to be frustrated by impossibly corrupt bureaucrats and artificial bottlenecks. Every company doing business in India has a repertoire of horror stories. On the respected Corruption Perceptions Index, with 0 signifying “highly corrupt” and 100 “no corruption,” in 2019 India scored 41, tied with Morocco, Ghana, Benin, and China. (I’m amazed they could tie with anyone.)

Still, I’m storing energy for a return. There are too many treasures in India to be dissuaded by scams at every turn.