China is arguably the most different country in the world for westerners. Its elaborate and sophisticated civilization developed over thousands of years, virtually isolated from western influence. Its language, writing, culture, customs, and thought share little with our own except our basic human natures. And therein lies its fascination.

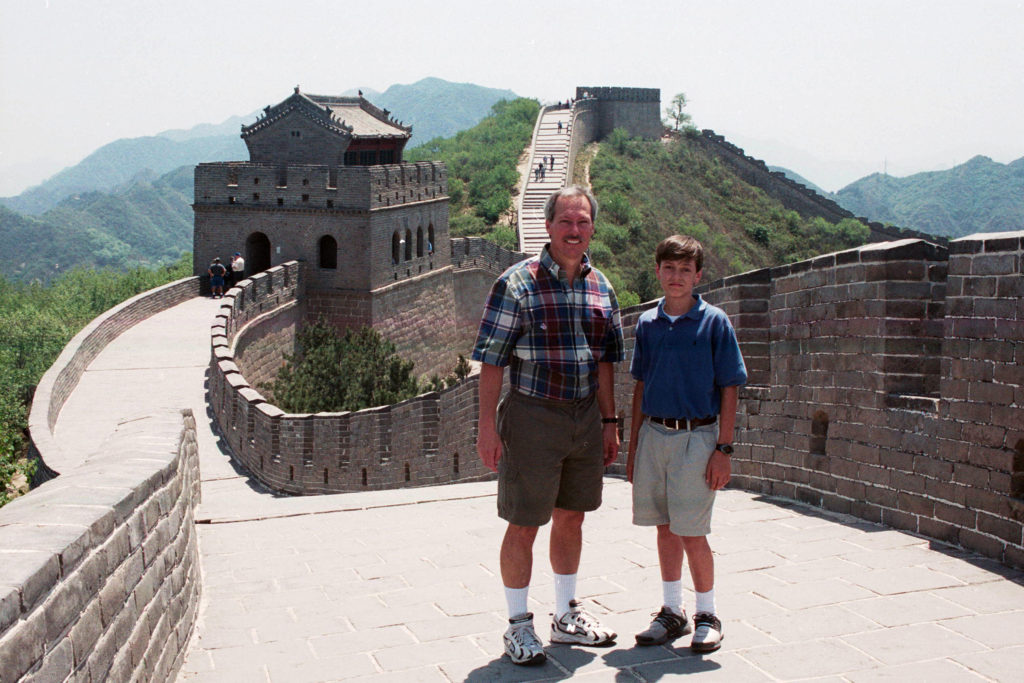

I promised my three sons that as each reached 12 years old, he could pick a place in the world and he and I would go there together. The first chose Germany, where we trekked through castles; the second took the Amazon River, where we stayed in camps beside the natives and fished for piranha. #3, Lee, wanted to see the Great Wall of China because “it’s the only man-made structure you can see from space.”

Where you can’t read the signs, independent travel isn’t an option, so we signed up for a two-week group tour.

Our hotel in Shanghai was a western-style high-rise, the only noticeable difference being the Chinese characters over the entrance. “5-star” we were told, but as with many things in China, “5-star” doesn’t mean 5-star. It was simple, modern, clean, new, and more than adequate for our purpose.

The skyline from our 21st floor room wasn’t what we expected from China; we were surrounded by high-rise towers. Looking across the Huangpu River, cranes, estimated (unscientifically) to be 18% of the world’s total, were putting up skyscrapers faster than taxi drivers could learn the streets. It was a construction explosion of historic proportion, transforming Shanghai into arguably the world’s most modern city.

But looking down into the immense shadows on the ground offered a stark contrast. Narrow trails wound through old neighborhoods, filling the spaces between the buildings looming over them.

After 25 hours of travel and at 4 am US time, we should have been exhausted, but this view, aided by my adrenaline and Lee’s youth, inspired us. Besides, it was afternoon in Shanghai, and we needed to make the 12-hour adjustment. A walk through the neighborhood would help.

Memorizing which tall building was ours, we set out into the maze. The neighborhood was more shantytown than classic hutong. “Hutongs” have similarly narrow and winding alleyways, but with centuries-old stone dwellings with tile roofs and open courtyards. This one was more make-shift, tin-roofed lean-tos.

The alleyways weren’t wide enough for a car, but enough for 2 bikes to pass. In the Shanghai heat, doors and windows were open, offering views into many spaces. The rooms were tiny; most had a small gas cookstove, a table, a few chairs, and a tube TV. Bicycles were parked safely just inside the door. What space remained formed a narrow path to a bedroom.

Outside, women crouched as only Asians can, washing dishes and pots, and pouring the dishwater into the alley. Laundry, “the Chinese national flag,” hung on bamboo poles over the alley. The air was thick with the smoke and smells of many people cooking in close quarters.

The next morning, we boarded a modern Chinese bus for the requisite temples and museums. The main arteries were new, many lanes wide, divided, and featured ornate streetlights, broad sidewalks, and plenty of signage. The intersecting side streets were the crowded ancient alleyways, with people bumping into each other like amoebae.

Buses and fancy Mercedes flew by along with hordes of bikers, many with cellphones to their ears. Men on 3-wheel bikes piled high with freight, like ants with loads that dwarf them, struggled to get momentum.

After the official tour, Lee and I set out on our own again and soon discovered an open-air wet market—“wet” because vendors throw water on the floors to wash off the blood, guts, and animal parts. Nearly every animal species was represented—ducks, geese, chickens, fish, turtles, snakes, snails, insects, pigeons, rabbits, pigs, marmots, civet cats—displayed in cages, with all the associated aromas. It was the antithesis of appetizing to us, but business was brisk. A Chinese friend later told us, “We eat everything with wings but airplanes and everything with legs but the table.”

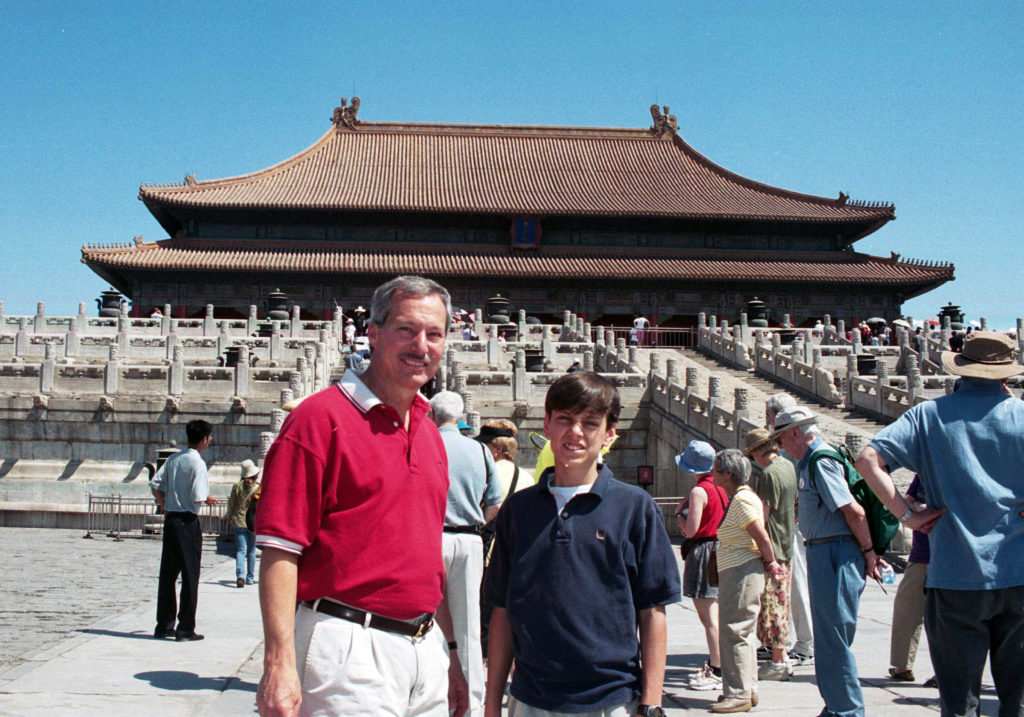

In Beijing, our tour took us to the purpose of our trip, the Great Wall, a structure so massive that even hordes of tourists couldn’t overwhelm it. A 2000-mile long, seemingly impenetrable, stone barrier built without modern tools tells of an incredibly organized, disciplined, and obedient civilization.

As we reloaded the bus I was talking to our guide when an Asian couple approached and asked in English where the entrance was. He turned and pointed. As they walked away, I asked if what they were looking for wasn’t where we had just come from—the opposite direction. He smiled and said, “They’re Japanese.” Every country has its own racism.

Back at the hotel, Lee and I caught a taxi to the Silk Market. The driver claimed his meter was broken, but the hotel bellman had already told us the fare should be 24 yuan. When we arrived, the driver typed 110 on his cellphone. I smiled and held out 24, but that only provoked profanities we didn’t understand. Without a common language, the argument was going nowhere—until I wrote the number from his taxi certificate on my hand; then the price quickly settled at 24. As we climbed out, he rolled down his window and said, “Soly, soly, soly, soly!” Only later did we figure out he was saying, “Sorry.”

The Silk Market was notorious for its counterfeits. At the time, it was an open-air flea market of more than 400 vendors selling knock-off Louis Vuitton, Prada, Gucci, Chanel, Armani, and more, all at fractions of their normal prices.

Lee and I chose North Face jackets and negotiated the price from $60 each to $12. We were assured they were the real thing and indeed they looked official, down to the label and tags. Perhaps it was only my suspicions that made them seem not to hold up well.

And we picked up a few $10 Rolexes. Lee’s school friends didn’t know to be impressed and I abandoned mine as a conflict in style, like a pig in lipstick. But a friend we gifted one to said it kept better time than his real one.

We jumped at an opportunity for a pedicab tour through a Beijing hutong, including a home visit with a Chinese family.

With all the stops and starts on the cobblestones and the twists and turns of the hutong alleyways, the young cyclist earned his fare.

The old stone dwellings were built against each other and extended to the edge of the street, making use of every square inch. Despite being centuries old, they were clean and neat, and many of the wooden doors had style.

Our hosts were an old couple, 94 and 92. The man smiled continuously and hardly spoke; his wife was outgoing with a sharp mind and impressive memory. They showed us around the home—a small stone courtyard with a large tree, surrounded by five stone rooms with wooden entrances.

Over Chinese tea and cookies, we asked through our translator what changes in their lives they remembered most and how they felt about them.

She recalled the Last Emperor and his abdication (1912), but said she was too young to understand its significance. They remembered hardships of two world wars and especially the Japanese occupation, although they were not within the occupied area “that was treated so brutally.” She recalled Mao Tse Tung and the Cultural Revolution, with the resulting starvation and economic deprivation; nevertheless, Mao remained one of their historical heroes. They endured the prohibition of religion, continuing to practice their Buddhism clandestinely. They considered the one-child policy “a necessary misfortune.” She was aware of the Tiananmen Square protests and deaths but politely declined to discuss it; our translator indicated that was wise.

“The biggest changes” had come with recent modernization. Specifically, their son and his family had moved “far, far away.” When we asked why, she explained that the son was now earning a good salary and had taken an apartment five miles away for more space. He visited often and gave them cellphones, but not having the entire extended family living with them in their hutong home was a shock to their traditional values.

They felt life in general was better now since they could afford many things that were out-of-reach before. Still, they missed the guaranteed employment, free medical care, and array of social benefits the government no longer provided.

After nearly two weeks together, “Michael” (the Anglicized name our guide went by) began to diverge from the official tour scripts and offer his personal opinions. He scoffed at Chinese newscasts and newspapers as not being remotely credible and said Chinese people “believe nothing in the newspaper but the date.”

Yet, he said, people get little other information as most other sources are blocked. Although he disagreed with many government policies, he felt organizing to push for change or express adverse opinions was out of the question as it almost always led to a prison sentence. Better to keep your head down and go along.

The trust he showed in us was moving but its potential consequences made us uncomfortable.

China Reflections: The Dragon Awakens

China is a paradox of civilization. It is 11th century lifestyle, living beside and in the shadow of the 21st. It’s raw and potent capitalism, designed and managed by communism. It’s unvarnished pursuit of self-interest, guided by the social morality of Confucius. It’s frenetic modernization in the world’s most traditional and longest-running civilization.

But it’s working.

Never in history has an economy developed as quickly. Never have the masses been plucked so suddenly from abject poverty and elevated to among the world’s most wealthy. Never have desolate slums been renovated into modern residences with such speed. Never has a country taken such a giant leap from the bottom of powerful nations to contend for the top.

Is China’s strange blend of capitalism and communism the secret sauce? Is China a model for the world to emulate?

In the 1970’s, China ranked among the world’s poorest countries, with a per capita income a third of sub-Saharan Africa’s. It was frequently held up as another real-world example of socialism not working as an economic system.

In 1979, China did an about-face. After years of fierce adversity to capitalism, it suddenly embraced it with passion. It not only permitted private enterprise, it sold ownership stakes in its SOEs (state owned enterprises), relinquished management of them, and nurtured the companies with loans, subsidies, and preferences.

It built fabulous infrastructure—new highways, bridges, high-speed railways, airports, terminals, ports, telecommunications, power plants and power transmission, etc.

It deferred legal restrictions and regulations—no EPA, no OSHA, no ERISA, no EEOC, no FMLA, no FTC, no FLSA, …and no intellectual property protection. The government not only turned a blind eye to violations, it allegedly sponsored and participated in the theft of intellectual property that its industries needed to catch up and compete with the developed world.

Such a sudden and complete reversal in economic policy could only happen in a system of powerful state control. Once China’s state apparatus decided on the new development strategy, it didn’t have to convince and assuage the populace, deal with messy and unpredictable elections, nor negotiate changes to laws. It simply announced new policies.

Illustrative of the government’s power was its 1990s removal of 1.5 million people and the destruction of more than 1,500 cities and villages and 1200 ancient archaeological sites along the Yangtze River to build the Three Gorges Dam. Any western country would still be in court, arguing the rights and abuses of individuals, animals, and insects.

Arguably the Chinese people benefit from the government’s unfettered focus on development, as more than six hundred million people have been lifted out of poverty.

Philosophers have long speculated that benevolent dictatorship is the most efficient form of government. Decisions are made by the most qualified, who study the options thoroughly and choose carefully which best benefit the people.

Communism, with its one-party system, subscribes to that philosophy. The Party makes unconstrained decisions that, in theory, are for the benefit of the people.

Democracy, in contrast, takes great pride in every person having a vote. Its process of debate, forming public consensus, and voting is painfully slow and often ugly, frequently leaving us divided and hamstrung.

Perhaps worst is that, instead of choosing the best ideas and the most capable candidates, we choose those that reflect the sentiments and education of the average voter.

(Many are surprised to learn that “one person, one vote” wasn’t what our founders had in mind. Originally, all thirteen states restricted voting to land and property owners. By the 1850s, some had changed the requirement to those who paid taxes. Both of those ideas would be anathema to citizenry today, illustrating that the concept of democracy is neither sacred nor settled.)

But benevolent dictatorship has a problem, illustrated repeatedly throughout history: it rarely remains benevolent. Dictators lose touch with the common people, fail to understand and empathize with their needs and wants, and eventually redirect their focus to their and their supporters’ self-interests—including, too often, empire building.

In China, the Communist Party hijacked what little voice the common people had by requiring Party approval of all local candidates. As the system became less responsive to the people, the Party found it necessary to suppress dissent, and eventually to restrict the news the people can access.

Despite its many inefficiencies and occasional poor choices, democracy is more satisfying and therefore more supportable because the people retain control—they’re part of the process (even when they wish they weren’t). Voters often make poor choices, but the choices are theirs.

And democracy has another advantage, perhaps more important for humanity. According to a popular theory, democracies rarely go to war except in self-defense. The argument goes that the common people are absorbed in their daily lives, have little interest in empire building, and are naturally averse to sending their sons off to war. When democracy is strong, leaders reflect those sentiments, and we’re less likely to kill each other.

Perhaps bumbling and inefficient democracy is indeed “the worst form of government, except for all the others.”